To reflect the theme of this year’s CQI and IRCA World Quality Week – Realising your competitive potential, Programme Lead, Chris Smith PCQI, looks at how you can employ Porter’s five forces of competitive position to gain a competitive advantage over your rivals.

Michael Porter’s five forces of competitive position

It is becoming more and more imperative to differentiate products/services from the competition than ever before, but with so many considerations and factors where should a company start this process?

A sometimes-overlooked methodology determined by Michael E Porter back in the 1980’s is often a very good starting point. The basic approach is outlined below.

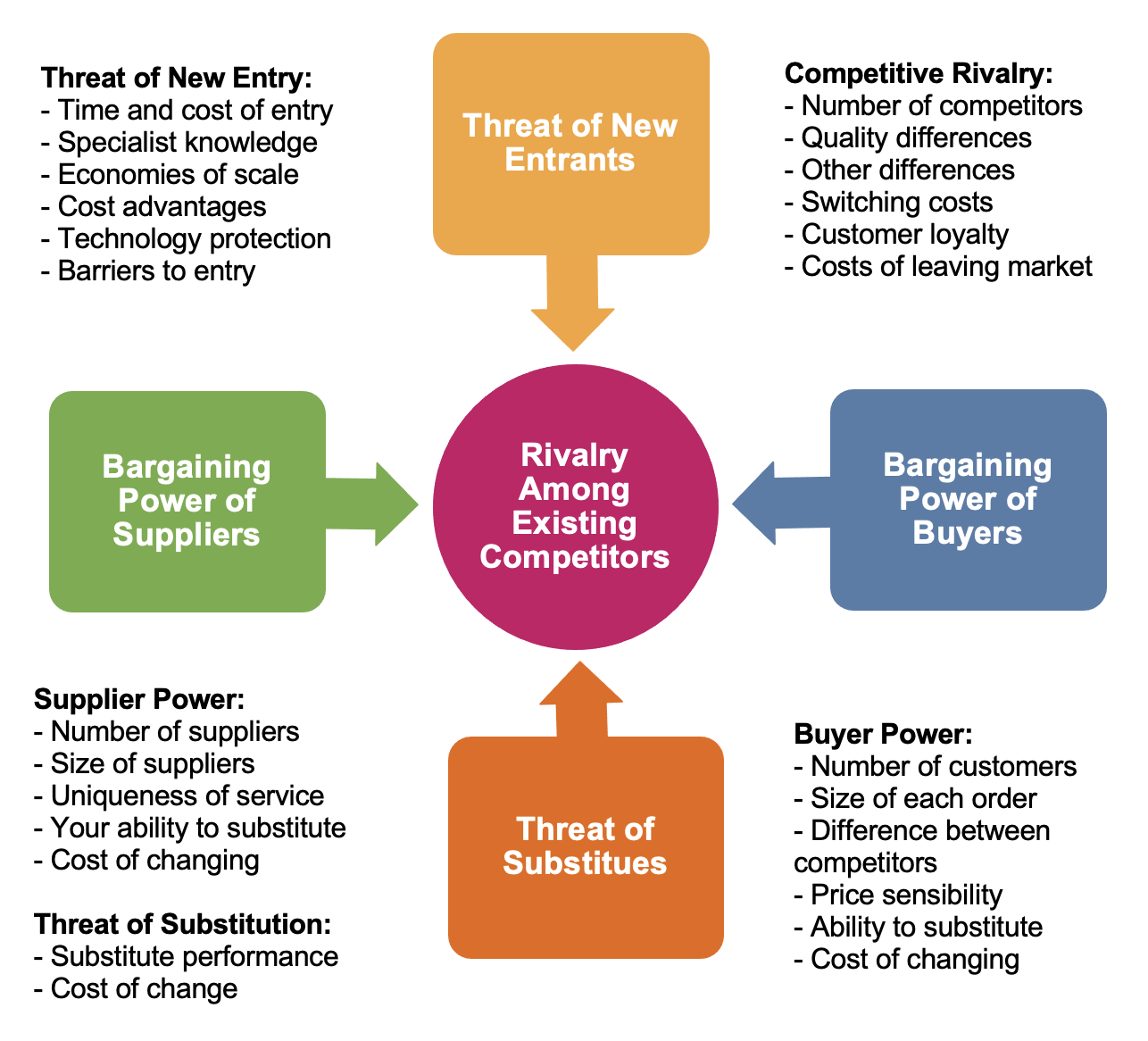

Porter identified five factors affecting the competitive position of a company. He argued that a company that wishes to improve its performance must take account of these five forces, before it can make a decision as to the best strategy for future success.

Porter five basic competitive forces are outlined below and can be used to determine the state of competition and its underlying competitiveness:

- The threat of new competitors entering the industry

- The intensity of rivalry among existing competitors

- The threat of substitute products or services

- The bargaining power of buyers

- The bargaining power of suppliers.

These five forces of competition can be used to determine the rate of return on invested capital (ROI) in industry, relative to the industry’s cost of capital. The strength of each of the competitive forces is determined by a number of key variables pertinent to the industry.

1: Threat of New Entrants

A major force shaping competition within an industry is the threat of new entrants. The threat of new entrants is a function of both barriers to entry and the reaction from existing competitors. There are several types of entry barriers:

- Economies of scale. Economies of scale act as barrier to entry by requiring the entrant to come on large scale, risking strong reaction from existing competitors, or alternatively to come in on a small scale accepting a cost disadvantage. Economies of scale refer to the decline in unit costs of a product or service.

- Product differentiation. Product differentiation creates a barrier to entry by forcing entrants to incur expenditure to overcome existing customer loyalties. New entrants must spend a great deal of money and time to overcome this barrier.

- Capital requirements. The capital costs of getting established in an industry can be so large as to discourage all but the largest companies.

- Cost advantages independent of scale. Existing companies may have cost advantages not available to potential entrants regardless of the entrant’s size. These advantages can include access to the best and cheapest raw materials, possession of patents and proprietary technological know-how, the benefits of learning and experience curve effects, having built and equipped plants years earlier at lower costs, favourable locations, and lower borrowing costs.

- Switching costs. Switching costs refer to the one-time costs that buyers of the industry’s outputs incur if they switch from one company’s products to another’s. To overcome the switching cost barrier, new entrants may have to offer buyers a bigger price cut or extra quality or service. All this can mean lower profit margins for new entrants.

- Access to distribution channels. Access to distribution channels can be barriers to entry because of the new entrants need to obtain distribution for its product. A new entrant may have to persuade the distribution channels to accept its product by providing extra incentives which reduce profits.

- Governmental and legal barriers. Government agencies can limit or even bar entry by requiring licenses and permits. National governments commonly use tariffs and trade restrictions to raise entry barriers for foreign companies.

The effectiveness of all these barriers to entry in excluding potential entrants depends upon the entrants’ expectation as to possible retaliation by established companies. Retaliation against a new entrant may take the form of aggressive price-cutting, increased advertising, or a variety of legal manoeuvres.

2: Threat of Substitutes

All companies compete with other industries offering substitute products or services. Steel producers are in competition with aluminium producers. Sugar producers are in competition with the companies which are introducing sugar-free products. The competitive force of closely-related substitute products impact sellers in several ways.

First, the presence of readily available and competitively priced substitutes places a ceiling on the prices companies in and industry can afford to charge without giving customers an incentive to switch to substitutes and thus eroding their own market position.

Another determinant of whether substitutes are a strong or weak competitive force is whether it is difficult or costly for customers to switch to substitutes to substitutes. Typical switching costs include; the cost of purchasing additional equipment, employees retraining costs, the time and costs to test the quality for technical help needed to make the changeover.

As a rule, the lower the price of substitutes and the higher the quality and performance of substitutes, the more intense are the competitive pressures posed by substitute products.

3: Bargaining Power of Buyers

Buyer power refers to the ability of customers of the industry to influence the price and terms of purchase.

The competitive strength of buyers can range from strong to weak. The buyers are powerful when:

- They are concentrated and buy in large volume.

- The buyer’s purchases are a sizable percentage of the selling industry’s total sales.

- The supplying industry is comprised of large numbers of relatively small sellers.

- The item being purchased is sufficiently standardized among sellers that not only can buyers find alternative sellers but also they can switch suppliers at virtually zero cost.

- The buyers pose a threat of integrating backward to make the industry’s product.

- The sellers pose little threat of forward integration into the product market of buyers.

- The products are unimportant to the quality of the customer’s product or service.

- It is economically feasible for buyers to follow the practice of purchasing the input from several suppliers rather that one.

These factors change with time and the companies choice of buyers-groups should be regarded as an important element in strategic decision-making.

4: Bargaining Power of Suppliers

Supplier power refers to the ability of providers of inputs to determine the price and terms of supply. Suppliers can exert power over a company’s industry by raising prices or reducing the quality of purchased goods and services, so reducing profitability.

The extent to which this potential impact is realized depends upon several factors; in general, a group of suppliers is more powerful if the following apply:

- It is dominated by a few companies and is more concentrated than the industry its sells to.

- When suppliers’ products are differentiated to such an extent that it is difficult or costly for buyers to switch from one supplier to another.

- When the buying companies are not important customers of the suppliers group.

- When the suppliers of an input do not have to compete with the substitute inputs of suppliers in other industries.

- When one or more suppliers pose a credible threat of forward integration into the business of the buyer industry.

- When the buying companies display no inclination toward backward integration into the suppliers’ business.

5: Rivalry Among Existing Companies

Rivalry refers to the degree to which companies respond to competitive moves of the other companies in the industry. Rivalry among existing companies may manifest itself in a number of ways such as; price competition, new products, increased levels of customer service, warranties and guarantees, advertising, better networks of wholesale distributors, and so on.

The degree of rivalry in and industry is a function of several interacting features:

- Rivalry tends to intensify as the number of competitors increases and as they companies become more equal in size and capability.

- Market rivalry is usually stronger when demand for the product is growing slowly.

- Competition is more intense when rival companies are tempted to use price cuts or other marketing tactics to boost unit volume.

- Rivalry is stronger when the costs incurred by customers to switch their purchases from one brand to another are low.

- Market rivalry increases in proportion to the size of the payoff from a successful strategic move.

- Market rivalry tends to be more vigorous when it costs more to get out of a business than to stay in and compete.

- Rivalry becomes more volatile and unpredictable the more diverse competitors are in terms of their strategies, their personalities, their corporate priorities, their resources, and their countries of origin.

- Rivalry increases when strong companies outside the industry acquire weak companies in the industry and launch aggressive, well-funded moves to transform their newly-acquired companies into major market contenders.

How can this help companies?

Porter’s model is designed to help companies choose the most promising strategy for their business. As outlined it does this by focusing attention on the competitive forces at work in the wider industry scene, not just the company’s internal resources and operational efficiency. Porter identified three generic strategies: competing on price; differentiating products and services by offering something not offered by competitors or focusing on a niche market; later he went on to consider the role of diversification as a strategy and the massive impact of the Internet. But he stresses that it is not enough just to gather information. Companies need to ask themselves how they can use competitive forces to their advantage and rewrite the rules of the industry.

So that is the challenge moving forward for individual companies and industry is to gain competitive advantage over their rivals! Or, to become another casualty.

Chris Smith, PCQI

Programme Lead, rove.

To find out about World Quality Week, visit the CQI and IRCA website, or search #WorldQualityWeek on social media.

If you’re interested in studying one of our CQI and IRCA Quality Management courses, you can find out more here.